French-Canadians have been present in the Lake Champlain Region since the late 1600s, Jane Whitmore began at our Pause Midi on February 16. During the nineteenth-century Quebec Diaspora, or “La Grande Émigration,” some 900,000 people left Quebec for the United States, seeking economic opportunities and a better life. Between 1860 and 1900, New England’s French-Canadian population skyrocketed, so that by 1900, fully 37 percent of North America’s French Canadians were living in the United States, most of them in New England.

Whitmore is a descendant of such immigrants–all eight of her own great-grandparents came from French Canada. As avolunteer at the Vermont Genealogy Library, Whitmore has helped many French-Canadian descendants trace their family history.

The Vermont Genealogy Library, she explained, has resources and experienced staff to help with this research. It was created in 1996 by the French-Canadian Genealogical Society to be a repository of data and to provide resources for individuals’ genealogical research. Since its founding it has moved and expanded four times.

Basic Steps

Tracing ancestry can seem like an overwhelming job. So Whitmore recommended that you start with what you know. Collect primary information like photos and all the paper information you can get your hands on. Look for family Bibles. Interview your relatives. See if anyone else has already done any research on your family.

To make it manageable, she offered some excellent counsel: research one person at a time. Pick one individual and then follow their trail back in time, their family, their ancestral line. Then go on to another.

Use the Internet, she recommended—Google your surname with the word “genealogy.” Digital resources like Ancestry.com and FamilySearch.org are indispensable. These are subscription-based websites, and if you are working at home, you have to pay to set up an account to use them. But if you are a member of the Vermont Genealogy Library, you can use them there for free.

Using the information you find, develop charts, like pedigree charts and fan charts. Some people like to use genealogical software to organize names and relationships, while others prefer more low-tech formats like spreadsheets and word processing.

The Library

The Genealogy Library offers more than free use of Ancestry.com. It has a collection of 5,000 books and journals. They are histories, collections of obituaries, registers of marriage and baptism, and much more, about not only French Canadians but also on Irish, Scottish, English, Native Americans.

Church records are rich in information and are especially helpful for French Canadian genealogy. They can take you back ten or twelve generations, even back to Europe. But not all resources are online, Whitmore emphasized. In fact, certain key sources are barred from digitization. Vermont Catholic parish records are essential for marriages and baptisms, but they will never be online, by the restrictions of the diocese. So volunteers have spent years painstakingly transcribed them into volumes known as répertoires (directories). So far there are sixty-five volumes, their contents organized by surname. You won’t find them online, but you will find them at the library.

The marriage records record the names of the parents of bride and groom, so using these records, you can continue back through the generations. Once you find your ancestors in Quebec, your can use Quebec resources to trace them further.

Whitmore also recommends that you check vital records in town offices. Censuses, land records, and the like provide lots of information.

Challenges

You must be ready to encounter challenges, Whitmore warned. Records can be hard to find, even nonexistent. Even Vermont town records are not always comprehensive for the early years, before 1860. Sometimes records contain errors or have conflicting information. Handwriting can be unclear. In church records, you may encounter language barriers, or sacramental writing, or legal language. You need problem-solving skills, Whitmore explained.

Another issue is name variations. Sometimes when several family members shared the same first and last names, they used the word dit, which means “also known as”: Elie dit Breton, Elie-Breton.

Many French Canadian names have been anglicized. Sometimes the immigrants they did so deliberately. Other times census takers, town clerks, just wrote down what they heard. You have to puzzle through names, Whitmore warned.

And images on Ancestry.com and Family Search.org are not always clear. She said Genealogie Quebec website is a good source, with better images. MyHeritage specializes in European family history. The best site for New England research, she said, is American Ancestors.

Library Membership

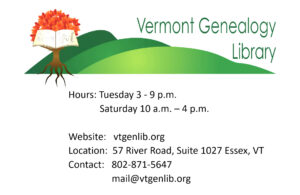

All these resources are available at the library. It costs ten dollars per day to use it; an annual membership costs forty dollars.

The library also offers classes, at ten dollars each. And if you are a member, you have access to recordings and handouts of past classes. Whitmore herself teaches classes there regularly. She also hosts a monthly special interest group for members with French-Canadian family ties.

Regardless of what a person’s heritage may be, Whitmore believes that tracing our ancestry is more than simply identifying our lineage. It can become a journey of discovery and appreciation for those who came before us. It helps us understand our own lives better.

Watch a video of the presentation on our YouTube channel.