Like many Americans who have traveled and/or lived in France, over the years I have visited a number of Gothic cathedrals, those in Paris, Chartres, Rouen, Saint Denis, Reims, Bourges and Beauvais. I have admired their high naves and lofty pointed arches, and tried to read the stories in their stained glass windows. I have been impressed by the large rose windows, learned the need for the flying buttresses, and appreciated the surviving Gothic statuary and painting. They became part of the French urban landscape for me, striking monuments to medieval religion, art, and architecture. They, and in particular Notre Dame de Paris prior to the tourist inundation, also served as temporary sanctuaries, places to sit quietly beside the urban hustle.

As years passed, they had largely faded off of my radar, a world of monuments in a country where the people and the daily ethos interest me more than impressive piles of stone containing art from centuries ago. In this context, I listened with interest to the AFLCR Pause Midi on Gothic cathedrals given by Robert Hajdu this past November. In his presentation, he mentioned, among other things, a sequence of dates for the better known Gothic cathedrals, all clustering in 12th and 13th centuries. Just as important, he noted that the cathedrals were largely limited to the region around Paris. Two questions emerged from this framework: why then and why there? The answers to these questions appear to involve a complex mix of feudal and religious politics, artisanship, geology, agriculture, climate, and epidemiology.

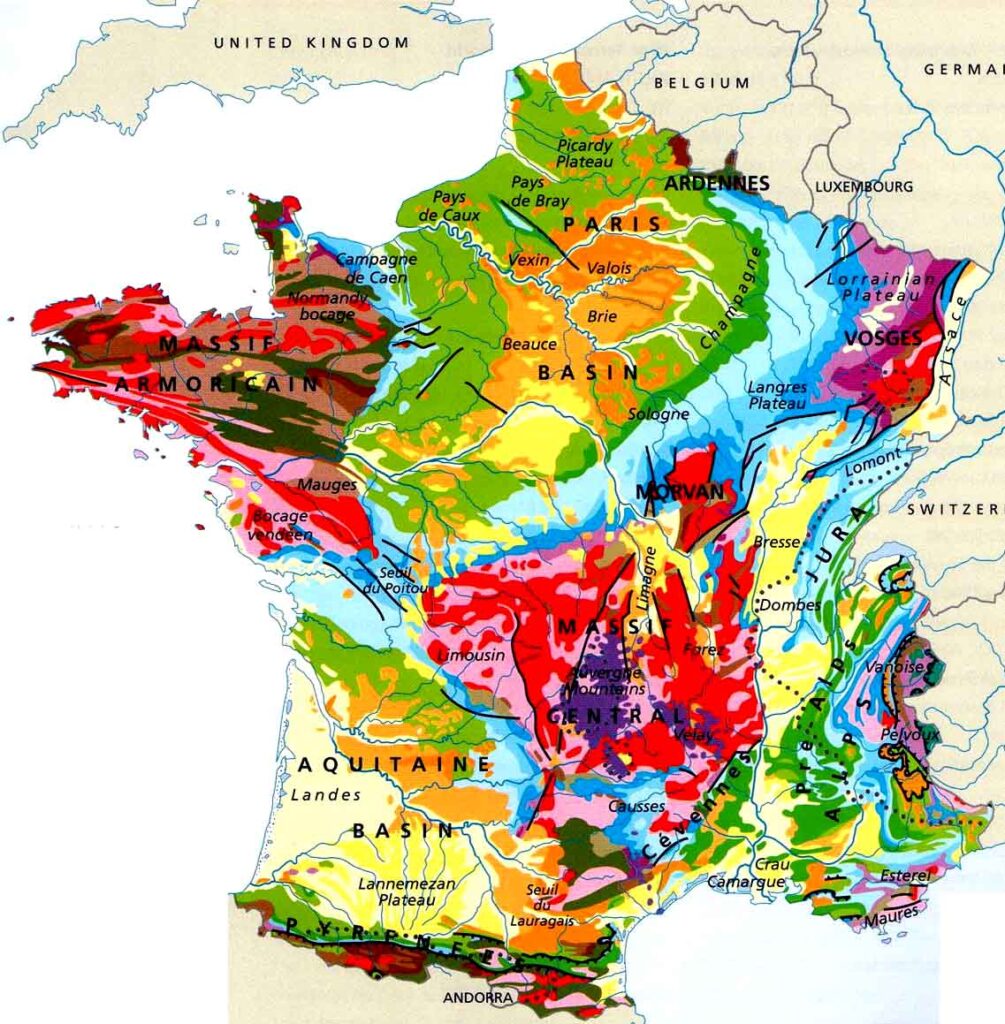

As noted by Hajdu, the overwhelming majority of Gothic cathedrals are found in northern France. At least 25 major Gothic churches survive there, of which two (Saint-Denis and Pontigny) were abbeys, one a reliquary (Sainte Chapelle), and the remainder cathedrals (the seats of bishops or archbishops). They extend across the Bassin Parisien, an area of flat to rolling fields, which is bounded by the Massif Amoricain to the west, the Massif Central to the south, the Massif des Vosges in the east, the Ardennes to the northeast, and the coast north and west. They are present across a number of the Provinces in the region, including the Île-de-France, Burgundy, Champagne, Picardy, Normandy, Touraine, and Poitou. Some of them are in major cities, such as those in Rouen, Tours, Paris, Reims, Amiens, and Dijon, but others are in smaller towns that were important seats in the later middle ages.

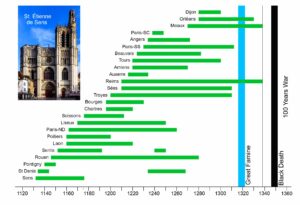

The first of the Gothic cathedrals, Saint Étienne de Sens (in Burgundy) began construction about 1130, closely followed by the Gothic renovations of the Saint Denis basilica (I have omitted the Autun and Noyon cathedrals, from 1120 and 1130 respectively, since they are considered transitional Romanesque-to-Gothic.) Construction, or the major rebuilding of Romanesque churches (as in Saint Denis, Rouen, and Angers), then continued through the 12th century and the first half of the 13th century; only those in Meaux, Orléans and Dijon were started later in the 13th century. Through time they tended to become taller and especially more elaborate, pushing the limits of Gothic design in, for example, Amiens and Beauvais. Given that most of them took decades to complete (at least their major portions), many of these towns saw ongoing Gothic church construction through much of the 12th and/or 13th centuries. Elsewhere in France, major Gothic construction was limited the cathedrals in Lyon (from 1180) and Toulouse (from 1210). Why did the Bassin Parisien in particular experience so much Gothic church building during this century and a half?

The increasing power of the Capetian kings in Paris may have led to this ecclesiastical building boom, as they asserted their feudal authority over the nobility of the surrounding provinces. However, a number of the Gothic churches were built, not by kings, but by abbots, bishops or archbishops, funded by local taxes, variably supported by the pope, and largely independent of secular authority. Moreover, the same period saw frequent military clashes between the French kings and that nobility, questioning the degree to which Paris exerted control outside of the Île-de-France. Yet, the 11th to the 13th centuries were a time of relative peace; the Viking threat had disappeared by the 10th century, and the bellicose tendencies of the royalty and nobility were directed in part into the Crusades.

Those centuries also saw unprecedented economic growth, especially north of the Alps, accompanied by substantial population increases and urbanization. This demographic surge has been attributed to major improvements in technology and agriculture, as well as to the warm climate (the Medieval Warm Period) prior to the subsequent global cooling (the Little Ice Age).

A series of technological developments, which had been coming together over the preceding centuries, matured and spread during the 10th to 13th centuries. Horizontal axis water mills emerged in the 10th century, and they were increasingly applied to tasks other than grinding grain. They were followed by effective windmills in the 10th century. The hand crank (first documented for the hurdy-gurdy) augmented power in artisan production through the 12th and 13th centuries. Springs to provide mechanical recoil were applied in the 13th century. These and other means of harnessing power joined advances in Gothic architectural design, ones enumerated by Hajdu. Those building elements included pointed arches, ribbed vaults, flying buttresses, and abundant windows, all of which lightened the walls and roofs and enabled the cathedrals’ heights and lights.

In agriculture the major advance for northern Europe, and in particular the Bassin Parisien, was the development and spread of the heavy plow. The region was covered during the Pleistocene by a thick layer of rich but heavy clay soil (loess), sediment that resisted the earlier scratch (or ard) plows and had limited agricultural expansion. The heavy plow—with a plowshare to cut the clayey soil horizontally, a coulter to cut it vertically, and a moldboard to turn the soil—enabled farmers to create high-ridged fields that functioned through both drought and rains. Heavy plows first appeared (documented through plow parts and ridged fields) about 1000, and evidence of them became widespread across the subsequent centuries. Although often pulled by oxen, these heavy plows were increasingly, and more efficiently, pulled by horses, once effective horse collars spread across Europe in the 12th century. These heavy plows are associated with the demographic expansion of the region, and the agricultural production they enabled would have been the basis for the wealth that made the Gothic building boom possible. They also enabled Louis IX to spend 275,000 livres (or about 30 million day-wages for skilled workers) on a crown of thorns, a reliquary, and the Sainte Chapelle in Paris.

Although most of these Gothic churches continued to be added onto through the 13th century, and all were modified in subsequent centuries, their major construction had largely ended by 1300. Of the ones started before 1250, only Notre Dame de Reims experienced substantial expansion into the 14th century. Several factors appear to have influenced this Gothic decline.

Climatically, global cooling (the Little Ice Age) began in the mid-13th century, possibly associated with the volcanic winter from the 1257 eruption of Samalas in Indonesia. By 1300 warm summers had become less regular across northern Europe, leading to localized famines in France in 1304, 1305 and 1310. They were followed in 1315 to 1317 when heavy rains and cool temperatures caused flooding and repeated crop failures, with the consequences creating shortages until 1322 or 1325 (the Great Famine). Northern France alone lost about 10 percent of its population and up 80 percent of its livestock. This Great Famine was followed by the beginning in 1337 of the Hundred Years’ War between France and England, with its consequent economic disruptions and military rural pillage. Bubonic plague then made its way across the Mediterranean and Europe, affecting the Bassin Parisien from 1348 to 1352; mortality from the Black Death there was between 30 and 60 percent.

The detailed reasons for the emergence and decline of Gothic cathedrals, basilicas, abbeys and chapels across the Bassin Parisien undoubtedly varied, but they would all have been tied into broader trends of politics, religion, economics, climate, and the technologies affecting crafts, agriculture and architecture. The specific circumstances would have to be determined for each structure, but the overall pattern holds.

Yet, when I next have the opportunity to sit quietly in a Gothic cathedral or abbey, I will continue admire the architecture and sense of light, as I have in the past. I will also remember the artisans and the peasants, the horses and the oxen, whose efforts generated the craft and agricultural wealth that made these edifices possible.

—Erik Trinkaus