Dates: 1926–

Role in AFLCR: co-founder; secretary; board member; member of executive committee that briefly succeeded Eric Bataille as president; chair of conversation groups committee

Simon Barenbaum was born in 1926 to parents who were itinerant actors in Jewish theater; the troupe happened to be in Latvia at the time of his birth. In the late 1930s they performed in Britain, where Simon attended school and learned English.

In June 1940 the Barenbaums were in Paris when the Nazis overran the city. All Jews had to register with French police, and those over 15 had to carry an identity card and wear a Star of David. Simon’s older brother was ordered to report to the French police. He did so but didn’t come home. Later the family were notified that he had been taken to a labor camp.

Concerned that Simon would be taken next, his father contacted a group of rescuers who transported the boy to a farm in Normandy, where he could live in hiding. But after two months, missing his parents, he returned to Paris.

In 1942 Simon and his parents were detained in Drancy, a transit camp on the outskirts of Paris. Here people were detained while awaiting their transport to “the east” and a fate unknown to them. Simon and his parents spent two months there and were soon to be deported, when a friend rescued them. He was a furrier and told the authorities that family were his employees and that he needed them to help make fur coats and boots for the Nazis, who had invaded the Soviet Union. In the fall of 1942 the family found themselves on a bus back to Paris.

There they quickly learned how to work with furs. That work, regarded as essential, protected them from being arrested and sent to another camp. It also protected the friend who had saved them.

Meanwhile Simon met up with some Jewish Boy Scouts who were making false ID cards. He obtained three of them for the family. They used them to leave for the south of France, to Draguignan, a town where they had some friends. On the train they had a second stroke of extraordinary luck: the German police who stopped the southbound train didn’t check their papers, so they got through safely.

In Draguignan, near Toulon, they lived a relatively normal life for two years. At one point the police drafted all young men to help the Nazis build a wooden stockade fence along the Mediterranean shore. Forced to report for duty, Simon and his friends deliberately worked with excruciating slowness.

In August 1944 American paratroopers landed in the area. Realizing that liberation was at hand, Simon, with his parents’ approval, went into town to look for ways to help the Americans—after all, he could speak English. There the head of the local Resistance gave him the mission of finding the Americans and explaining the military situation to them: that while the French had liberated the center of town and had rifles, the Nazis were on the hill with machine guns.

That night Simon and another Resistance member set out along the road to find the Americans. Finally in the darkness they encountered two lines of the paratroopers. Simon explained to them that the Nazis were occupying the high ground and the French needed help. Then he led them to a position just above the Germans. In the morning the Americans attacked the German camp.

Simon did a few more missions with the paratroopers, like gathering supplies that American gliders had dropped in a nearby woods. After that, he acted a guide for an American unit that was moving up the Rhône valley. In Briançon, he carried information between the American and French forces, averting a Nazi attack.

After that Simon returned to Draguignan and attended school. Around this time the family got news that Simon’s elder brother had died at Auschwitz.

When the war was over, the family returned to Paris. In 1950 Simon moved to the United States, intending to teach French. He earned his Ph.D. at Brown University, then became a professor, teaching French first at Brown, then at Oberlin College from 1956, then at Middlebury from 1970. In the mid-1950s he married Ruth Schwarzkopf, a peace activist who was the daughter of Gen. Norman Schwarzkopf.

At Middlebury, he assigned his students a January term project to create a travel guide to Montreal. The result was “Vous allez à Montréal?,” a free 20-page booklet in French. It detailed walking tours in neighborhoods in old Montreal, Chinatown, the Boulevard Saint-Laurent, and more, pointing out local highlights. According to Barenbaum, “Here in Vermont and northern New York state, we are so close to Montreal, which is the largest French-speaking city in North America. ‘Vous allez à Montréal?’ encourages students who are studying French to take advantage of this wonderful, nearby resource.”

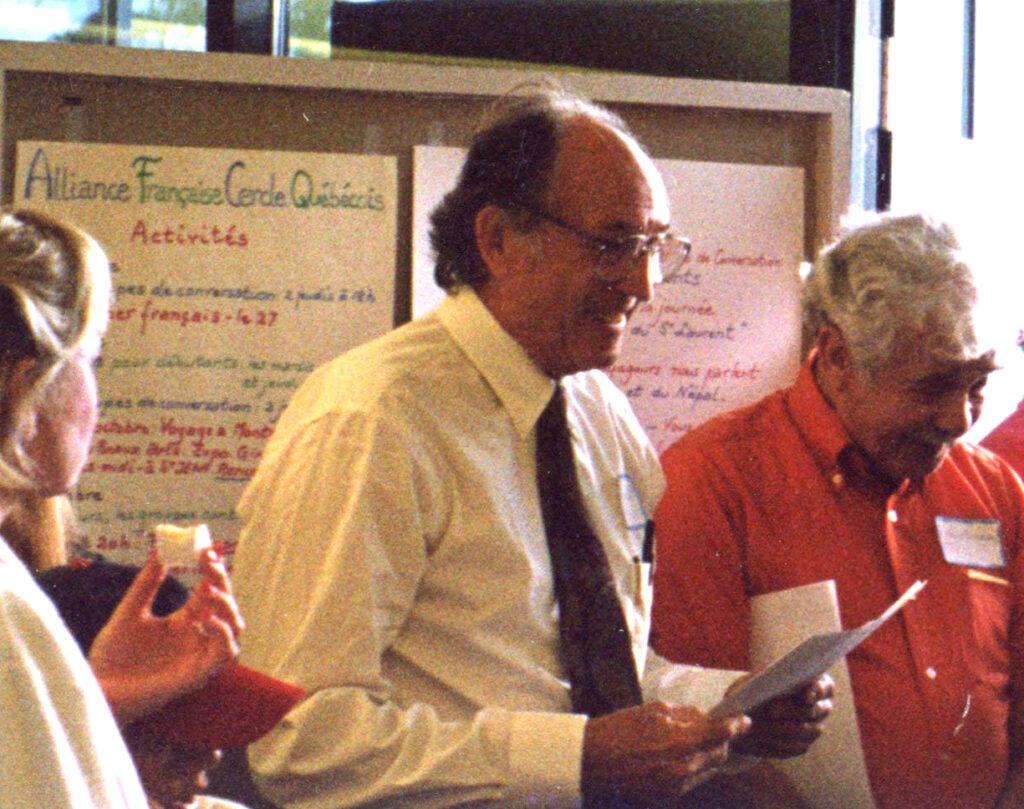

After he retired from Middlebury in 1992, he launched himself into a new career: promoting Francophony in northern Vermont. That was the year he joined Eric Bataille in founding the Alliance Française of Vermont—Cercle Quebecois, later refounded as the AFLCR in 2002. He served on the board and as secretary; executive committee member; chair of the conversation groups committee.

But his contributions to the AFLCR were just one aspect of his drive to promote French in northern Vermont. In 1992 he initiated “Les Boulangers,” a French conversation group that met weekly in a bakery in Bristol—it still meets in Middlebury on Saturdays. He edited the newsletter Ne laissez pas rouiller votre français, then later Activités francophones (below is the February 2015 issue), announcing Francophone activities and events in northern Vermont and the Montreal area.

He created a monthly televised Chronique Francophone, for Middlebury Community Television, with himself at the anchor desk, announcing notable Francophone activities. (Here and here are some episodes from 2016 and 2017.) He updated the Montreal travel booklet annually until 2007, which required him to pound the sidewalks of that beautiful Francophone city every spring.

His colleague Maurice Langevin said it wasn’t unusual for Simon to call him just to tell him about a new French film, or an art exhibit, or a theatrical production. He organized “Chez Roland” social lunches in Rutland and Burlington. He loved to sing and to teach people French songs—he sang while bicycling along the Saint Lawrence and in France. He liberally loaned out his copies of French novels, articles, and videos. It’s almost as if teaching French were his religion.

In 1999 the Vermont Chapter of the American Association of Teachers of French awarded him “Ambassador of French,” “for his services to the cause of teaching French.”

But even as he worked tirelessly to encourage and promote Francophony, he also spoke frequently to students at Vermont high schools, to share firsthand his experience of surviving the Holocaust.

Addiitonal sources:

Simon Barenbaum, “Underground in France,” In The Holocaust: Personal Accounts, ed. David Scrase and Wolfgang Mieder. Burlington, Vt.: UVM Center for Holocaust Studies, 2001.

Denise Bérubé-Mayone, Maurice Langevin, John Roberts, and Hildgund Schaefer, “Un grand merci à Simon Barenbaum,” Vermont Foreign Language Association, Fall 1999.

“Honneur à un ‘Ambassadeur du français,’” France-Amérique, April 1999.

“Simon Barenbaum honoré,” Le Richelieu, July 11, 1999.

—Janet Biehl

Thanks to Nicole Barenbaum for help with research.