I have had discussions with members of the AFLCR in which there has been confusion regarding the geographical and administrative regions of France. Those divisions are often unclear from the outside, and the French alternate between different systems and combine them. Given the frequent references to these areas of France, it appears worthwhile to explain and comment on them briefly.

The current situation is the product of a complex historical process, principally one in which the central government of France (based in Paris) has attempted to administer the remainder of the country. For excellent reviews of this process from the eighteenth century and into the twentieth one, I strongly recommend The Discovery of France by Graham Robb and a sociological history of this period, Peasants into Frenchmen by Eugen Weber.

The Provinces of France

France was initially divided into a series of provinces of varying sizes. Those provinces emerged through Middle Ages as members of the aristocracy established themselves and maintained control of their territories. Initially most of the provinces were largely independent entities; they increasingly fell under the control of the kings of France based in Paris and then Versailles. At the time of the French Revolution, there were about three dozen of them. They included well-known larger regions, such as Île-de-France, Burgundy, Aquitaine, Provence, Languedoc, Limousin, Normandy, Brittany, Alsace, Auvergne, and Lorraine, as well a suite of smaller ones. The actual boundaries of the provinces were determined by centuries of feudal negotiations and varied with time.

Many of these provinces circumscribed naturally defined agricultural areas and their hinterlands, and as a result, they tended to have some degree of cultural uniformity. In the east, west, and southwest, Alsace, Brittany, and the Pays Basque were also distinguished by linguistic differences. Yet until the late nineteenth century, relatively few of the peoples within France spoke French or saw themselves primarily as Frenchmen. They spoke a variety of dialects (or patois), many of them variants of Occitan (hence Languedoc) in southern France. They therefore perceived their identities primarily within their regions rather than with respect to France as a whole.

The Departments of France

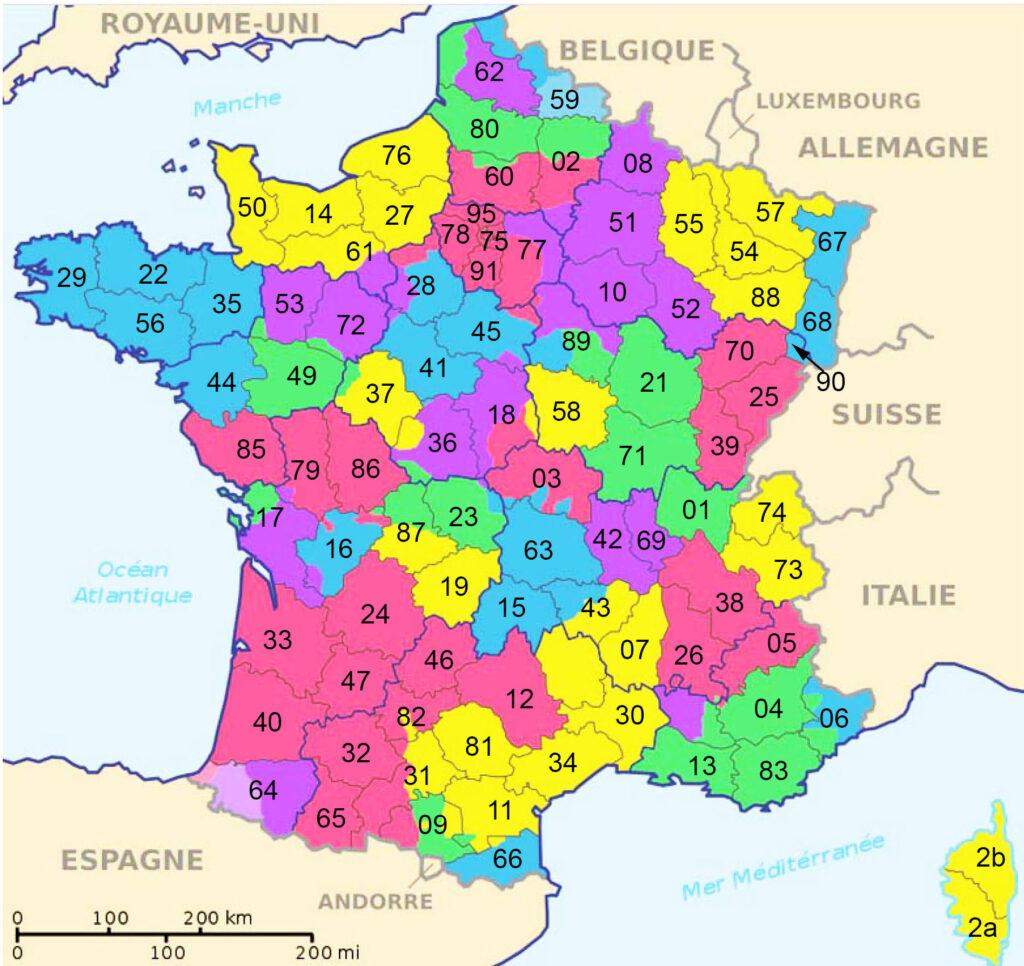

In 1790 the French revolutionary government sought to break up the traditional regions, to counter the established aristocratic control of portions of France and produce greater integration across the country. To this end, they divided the country into a series of départements. Initially there were 89 departments, each one centered around a town or city of some size. In 1922 Belfort was added, and then in 1968, to account for the population expansion surrounding Paris (les banlieues), five more were added, bringing the total to 95. In 1946 and 2009, five French colonial possessions became departments (Départements Outre Mer, or DOM). The departments were named after geographical features that they encompassed, principally rivers. For example, the department of Paris was Seine (now Paris), that of Bordeaux Gironde, that of Lyon Rhône, and that around Marseille Bouches-du-Rhône. Others were named after mountains (for example Jura, Hautes-Alpes, Hautes-Pyrénées, and Vosges), ones along the coasts were given names with Maritime as a suffix (for example, Alpes-Maritime, Charente-Maritime, and Seine-Maritime), and a couple of names referred to a geographical location (for example, Finistère and Nord).

To further organize the departments, the initial eighty-nine were numbered alphabetically, beginning with Ain (01) and Aisne (02) and ending with Vosges (88) and Yonne (89). To these were added Belfort (90) and the banlieues around Paris (91 to 95). Major cities and their urban areas became known as a result by their departmental numbers, hence 13 for Marseille, 31 for Toulouse, 33 for Bordeaux, 75 for Paris, and 69 for Lyon (although Rhône is now divided into 69D for the department and 69M for Lyon-Metropolis). There are nonetheless a few exceptions to the alphabetical sequence. For example, Yvelines, to the immediate west of Paris, is 78, following on Paris (75), Seine-Maritime (76) and Seine-et-Marne (77). Deux-Sèvres (79) is just before Somme (80), yet Bouches-du-Rhône (13) follows Aveyron (12) rather than Rhône (69).

One consequence of the alphabetical arrangement of departmental codes is that there is little geographical order to the numbers. Adjacent similarly named departments have sequential numbers, as in Charente (16) and Charente-Maritime (17) and as in Eure (27) and Eure-et-Loire (28). Yet Ain (01) is in the central east next to Switzerland, whereas Aisne (02) is the north next to Belgium. Bouches-de-Rhône (13) is on the Mediterranean, whereas Calvados (14) is northwest along the channel. One simply has to learn both the names and the numbers of the departments as one becomes familiar with them.

These numbers are part of the French postal codes, in that the postal codes start with the two digits from the departmental designation. The departmental numbers were also, until 2009, a prominent part of vehicular license plate numbers. Aside from an administrative role, those numbers enabled drivers to correctly direct unprintable comments at offending drivers, reinforcing regional animosities through plate prejudices. It is not all negative—once in Bordeaux I was asked about the weather in Paris; my rental car had a 75 license plate. The more recent plates retain the departmental number, along with the departmental symbol, but it is in smaller font and can be changed if one moves.

The Regions of France

In addition, the departments of France are organized into eighteen régions, twelve in mainland France (l’hexagon) plus Corsica and five overseas. They serve an administrative role, in between the national government and the departments. Created in the 1980s, they have undergone several revisions since then.

The Provinces and Departments in Common Usage

Despite the elimination of the provinces of the ancien régime in 1790, the names continue to be actively used in France for regional designations. For example, a number of the appellations for wine refer to provinces (for example, Champagne, Burgundy, Provence, and Roussillon). Similar terms apply to breeds of domestic animals (for example, Limousin and Blonde d’Aquitaine cattle).

The province names also apply to many personal identities. A person from Montignac (where Lascaux is located in the Dordogne department) would never self-identify as a Dordognais.e (if the term even exists); s/he is a Périgordien.ne. Someone from Limoges is not an Haute-Viennois.e; s/he is a Limousin.e. A native of Poitiers is similarly not a Viennois.e (that applies to people from Vienna, Austria); s/he is a Poitevin.e. Yet people from Angoulême are referred to as Charentais.e (and no longer Angoumois.e), and the football/soccer team in Bordeaux is les Girondins.

Old affiliations persist—I once heard a argument against the departmental system from someone from Cognac, because Cognac was originally part of the province of Saintonge (with Saintes, now in Charente-Maritime) but is now in the department of Charente with Angoulême (formerly the center of the province of Angoumois). For a more practical reason, a colleague who lived in Chantilly, north of Paris, argued that his daughter should go to the University of Paris, given that Chantilly is in the Île-de-France province, but at that time would have had to go to the University of Amiens, given that Chantilly is now in the Oise department.

Closer to my own experience, the antiquities directorate for the southwest of France (part of the Ministère de la Culture)is the Circonscription d’Aquitaine. The similar administration for the central western region of France is designated the Circonscription de Poitou-Charentes, combining the earlier province of Poitou with the departments of Charente and Charente-Maritime. The antiquities museum is Bordeaux is also known as the Musée d’Aquitaine.

A further reflection of the persistence of the provinces is in the geological map of France, published by the Institut Géologique de France. The regions are labeled principally using the names of the provinces (none of the departmental names), which emphasizes the degree to which those areas were environmentally, as well as humanly, circumscribed.

More examples could be provided. However, the main point is that France, for many practical (and cultural) reasons (if not administrative ones), continues to be divided by both the provincial boundaries of the ancien régime and the departmental borders of the French Revolution. If one searches for a place in France in Wikipedia, one will be provided with the département and sometimes the région within which it falls. The province is not furnished. Yet to the French, the old provinces still represent regional and cultural aspects of primary importance. Consequently, being aware of the provinces and departments of France, and understanding some of the ways in which they interweave, can only help in appreciating France and communicating with people for whom this is an essential part of their history and culture.

—Erik Trinkaus

Map credit: Modified from Wikipedia.